Julia scratched the dry skin that was pulled tightly under her braid. She knew she should unbraid, brush, re-braid her hair, probably wash it as well, but the dark, graying mass was unwieldy and annoying. Perhaps she should just shave it off. She could wrap her bald, scraped-clean and scabby head in one of Aunt Sally’s long-outdated scarves when she made the weekly trip to the grocery store. It wasn’t as if anyone was looking at her, anyway.

“Julia? Julia!”

Julia sighed, not even trying to muffle the sound as she stood, supporting herself on the edge of the kitchen table with one hand and on the back of the chair with the other. When did she start to feel so old, to feel some dark affinity with the figure in the first floor bedroom, the atrophy in her muscles and joints a prophecy of what was to come?

She didn’t bother to call out to Aunt Sally as she made her way through the living room and into the small, makeshift bedroom that had once been a sleeping porch. What the hell did anyone need with a sleeping porch, anyway? She supposed that Aunt Sally, or more likely Uncle Kermit, had just enclosed the v-shaped edge of the house with windows when they updated the bungalow back in what, the 1950s, and thought it sounded upscale to refer to it as a sleeping porch. Whatever it was, it still stank of Uncle Kermit’s fake Cuban cigars and the dampness of sweaty feet. Julia regularly sprayed Febreeze and some sort of orange oil she bought at Home Depot that was supposed to eliminate particularly trying odors, and for a time, they helped., especially the orange oil, helped. Something about the orange oil was soothing to Julia, and she often carried the can throughout the wilting house and sprayed the uplifting contents randomly into the dusty air. She caught herself, eyes closed, inhaling deeply during these moments, and wondered what in the hell was wrong with her. Jesus Christ, she would shake herself, and rub her forehead as if the answer would come to the surface of her brain with just the right amount of physical stimulation.

“I’m here, Aunt Sally.”

Julia wiggled her toes as she made herself as comfortable as she could in the wicker-framed chair that had stood beside Aunt Sally’s bed for nearly two decades. The cushion, flowered and faded, was mushy and flat, but Julia didn’t care enough about it to purchase another. She didn’t care about much anymore.

The older lady reached out a wrinkled hand, the nails painted a soft, Barbie pink that had begun to chip. Julia automatically took hold of it with her own.

“I’ve a yen for that pizza with those itty bitty pepperonis that are all crispy on the top.”

Aunt Sally’s eyes were filmed over, and Julia wasn’t too sure just how much her predecessor’s sight allowed her to perceive. Aunt Sally’s head was turned in her direction, though, and Julia thought that just maybe Aunt Sally could see her, perhaps even see her more clearly than Julia had been suspecting. Julia nodded and smiled in spite of herself. She and Aunt Sally shared the same preference in pizza toppings.

“Fiesta. I’ll give them a call and run down to pick it up. Just pizza? Anything else?”

Aunt Sally shook her head and pulled her hand from Julia’s, the pink nails curling inside a fist before disappearing completely underneath the quilt that was almost always pulled up to Aunt Sally’s chin. Julia’s mother and Aunt Sally had made that quilt together decades ago, and Aunt Sally had an emotional attachment to it. She whined pathetically when Julia insisted on washing it once a week, complaining that the other blankets were scratchy and thin. In the heat of the simmering Ohio summer, Aunt Sally would struggle physically with Julia as Julia tugged the quilt from Aunt Sally’s surprisingly strong grip, tears in the yellowed whites of her eyes.

“Aunt Sally, you’re sweating buckets, and it’s not healthy for you to be swaddled up in this heavy thing.”

Aunt Sally had growledtaken to growling at Julia once, and Julia had let go and stepped back in shock.

“‘This heavy thing,’ I’ll have you know, is all I have of your mother. When Sarah comes for me, I want her to see that I haven’t forgotten her, that I’ve still held onto this quilt of ours. Back off, missy. Just. Back. Off.”

It took an awful lot of persuasion, and reminders that every time Julia had taken the quilt away to wash it, she had indeed brought it back, to get the quilt off that bed. It was stringy and grubby and smelled of Aunt Sally, of armpit sweat and baby powder and the Anbesol Aunt Sally rubbed into her sore gums. Julia had noticed recently that it also carried the aroma of Absorbine, appalled with the realization that her own odors had become part of Aunt Sally’s heirloom rag. She rubbed her hands up and down her arms, noticing that the air had become chilly in the bedroom, and stood, determined not to use the rough wicker armrests as leverage by keeping her hands on her arms. She had to make a concerted effort not to grunt as she leaned forward and shifted her weight upwards.

Aunt Sally blinked and wrinkled her nose, her shriveled lips twisting to the side as she did so.

“Some of that slaw. I like the way they make it, with mayonnaise. Not too sour.”

The old woman licked her lips and Julia felt her stomach churn, both with revulsion and hunger. She was fond of Fiesta’s cole slaw as well. It concerned her that she and her aunt shared the same taste in slaw as well as pizza. She nodded and walked away, sure that her aunt wouldn’t mind that she left the room without telling her. Aunt Sally might have been physically limited, but her mind was quick, and she would know that Julia was leaving to order the food, and then, soon after, to drive over and pick it up.

Julia didn’t feel like leaving the house, but knew itf was better for her to get out more than once a week for grocery shopping. The doctor’s visits were too occasional to count, and the visiting nurse stopped by every ten days or so to check up on Aunt Sally. Lately the nurse had started to ask Julia about her own health, which was annoying. Considerate, Julia understood, but annoying. As if she herself were getting old.

“Yes, I’d like to order a large pepperoni pizza. Yes, I’d like a pint of cole slaw as well. Yes. Yes. Julia. Thank you.”

Fiesta was a loud, hot take-out business that had been in the area for a good part of Julia’s life. There were three or four around, one in the neighborhood, one a little farther out, and two a bit far for Julia’s taste but still in the county. The one a little farther out had little pepperonis that curled as they baked in the oven. They had made Julia’s exile to this tiny house on a quiet street a little more palatable (oh, could she laugh even at her choice of words) over the years. At least once a month Aunt Sally asked for Fiesta, and Julia found that she sometimes dreamt of the tiny circles of meat, the dripping grease, the thin dark outline of the pepperoni that stretched up and away from the cheese. Julia could have eaten that pizza every day, but she knew it wouldn’t be good for the dimples that had crept up along the backs of her thighs, or for the soft flesh that had formed above her hip bones. Once she had been thin, her legs long and brown in the sun, and boys had spoken sweet words and touched the bones at her back above her waist with their warm, persuasive fingers. Back then she had never seen a curled slice of pepperoni, had never feasted on crunchy, tangy slaw. She had been the food, the fruit;, she had been the one tasted.

Julia stood at the kitchen window, watching a group of children as they stepped from the school bus and pushed at each other, walking, skipping in the middle of the street towards their homes. She could have been a mother, once. Maybe she would have liked that, to care for a child instead of an old woman, to watch growth, accomplishment, to find acceptance in the fresh, clean face of a new little person who had begun his life within her. But no, that had been a long time ago, and she had given that chance to another, another who had gladly taken the new life and for all Julia knew, still held that child, now long grown, close to her heart. She shrugged the stiffness from her shoulders and stepped back, rubbing her hand under her nose.

“Going to Fiesta,” she called loudly, facing the living room, unsure if her voice had carried into the sleeping porch. Aunt Sally did not reply. She might not have heard, Julia considered. She might be asleep. She might be dead. All of these possibilities meant little to her. She would live here in Aunt Sally’s house until she herself was dead, dead in her bed in her mother’s old bedroom at the top of the stairs, dead on the couch where she took a nap every afternoon, dead at the kitchen table where she drank her coffee every morning and sometimes a rum and Coke on a hot summer evening. All of those possibilities meant little to her as well.

Kerry Sutherland is a librarian and a PhD in American literature as well as a published author of poetry, fiction, creative non-fiction, and professional pieces. She likes cats, anime, NASCAR, and Henry James. Like the women in this story, she loves Fiesta’s pepperoni pizza.

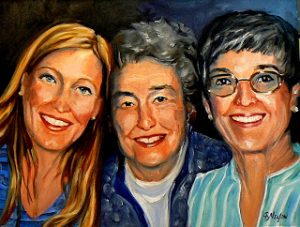

Three Generations by Carol Nelson